Change is good, if managed properly. Tenants relocate on average once every ten years and a project manager’s role is to guide and manage expectations so a seemingly overwhelming process becomes a pleasant experience. We watch the tenant’s money and project scope to assure best value for every dollar.

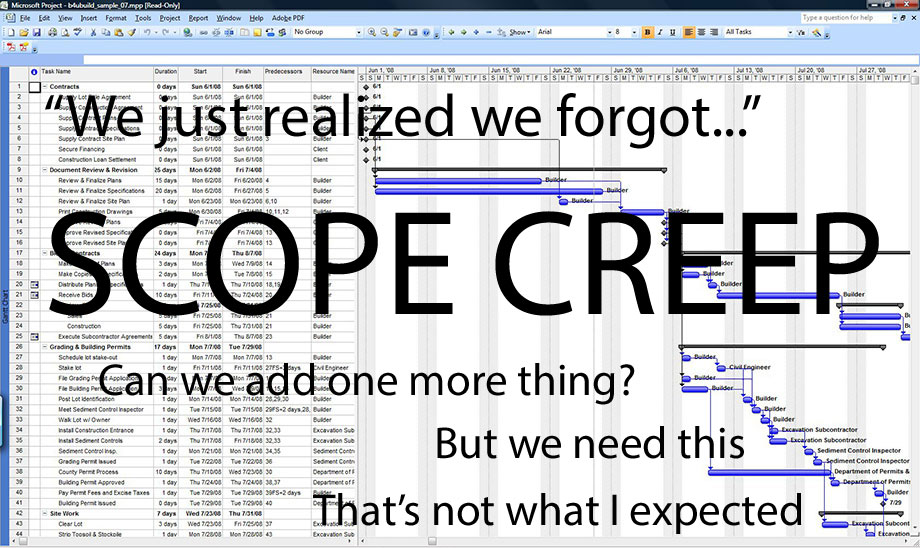

Scope Creep is often a term introduced into the project when intended or unintended changes arise that are beyond the original planning. This can occur at any stage in planning, design, construction and relocation. And if not identified and rectified early, it can impact your budget. The surprised tenant doesn’t necessarily hear “scope creep” but rather “$$ creep”.

The key to controlling scope creep is realizing it as a symptom, identifying the problem, assigning responsibility and mitigating its impact both on the schedule and budget. Scope creep does not necessarily mean an increase in the project size or budget, but can also be a result of the tenant’s design and budget revisions well after the plans have been approved. For instance, simple changes like adding power and data to a conference room table after construction is underway affects electrical, data, flooring and furniture plans and the resulting change order can cost upwards of $1,500. This can be addressed early in the design phase. Another example is taking delivery of furniture and finding out the modesty panels are covering your electrical and data outlets. Why? Because nobody checked with the furniture vendor or examined existing furniture that was relocated. Other issues may be out of your control such as HVAC systems not fitting properly in ceilings maybe due to existing ceiling joists or plumbing.

To minimize scope creep, you start with a detailed project program which creates a baseline that the project is measured by throughout the design, construction and relocation process. The program is created at the conceptual stage and includes objectives and goals, specific details and expectations. The stakeholders, management, vendors, maintenance staff, operations, accounting departments and all users should be involved in the process from the start. We ascertain general expectations and details right down to whether they want bottled or bottleless water dispensers which may require a water line added to the plan.

Design teams may fix problems which can sometimes lead to un-funded scope creep. Similarly, client’s can add items blindly thinking there is no additional cost. For every scope change, the client may need to find the money in the budget, so design teams are crucial here to help find acceptable and less expensive alternatives to costly products that may aid in preventing scope creep.

The client should have thorough interaction with the design team and project manager during space programming, design, construction and relocation planning and sign-off during each phase. Conduct reviews at various stages of the project so all parties can agree on scope, budget and schedule before proceeding to the next stage.

Once the construction documents are completed and construction begins, change order requests may ultimately need to be approved for unforeseen conditions or building department requirements. While scope creep may be a reality to the process, having a transparent, open dialogue and change management process for the whole team where everyone contributes for the benefit of the project is crucial to maintain quality control.

So yes, change may actually be good if the tenant can reflect back on the project after completion and know it was built right and fiscally prudent. Building it wrong so it’s on time and on budget is un-satisfying for everyone. If you proceed with a project manager at the helm and follow the project plan, the CEO, CFO, and all the other C’s will reap the benefits of planning that was orchestrated so that everyone was in sync.

Discover more from Helping NYC & Long Island Commercial Tenants, Owners, and Developers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Very good article. As a project manager and design build contractor I have had the project creep issue many times. You covered the topic well and I agree with your statement that you need a detailed and well thought out plan before you start. I have tried to explain that to customers and recently have had an issue with a project going over budget due to the customer adding work and not asking for an estimated cost and being suprised at the cost because they didn’t understand the amount of time and materials it would take. Making sure the customer gets a estimate even if they don’t ask for one can save alot of misunderstanding at the end. Again very good article.

I like to identify ‘must-haves’ and ‘nice-to-haves’ with client upfront and provide pricing alternates in bid documents to help save time if bids come in higher than approved budget — or get the CM on board early as BCCI points out to help with costing out alternates. I agree it is critical to obtain client sign-off at each phase of design prior to bid documents to effectively manage client expectations.

A great description of scope creep that all stake holders should read so they understand what is involved with a large project. I’m a Facilities leader that works closely with the project managers (PM) on projects in my buildings and understand what the PM’s have to deal with and how to explain to the stakeholders about changes after the project start.

Great post! Hiring the project team (architect, MEPS engineers, general contractor, furniture vendor, A/V consultant, cabling vendor, kitchen consultant, etc.) early on at the conceptual phase of a project adds significant value to the Owner/end user. It allows the team to align program, design, and budget expectations up front so that informed decisions – on everything from material selection to where power outlets should be located – can be made long before the start of construction. Identifying constructability issues and design conflicts before construction drawings are complete is also key to keeping the budget on target and avoiding scope changes and cost creep. Waiting to value engineer a project later in the game risks delaying the start of construction, which has its own cost implications.

That sums it up perfectly.